Palazzo della Ragione

A true miracle of architectural audacity and an impressive collection of fourteenth-century mural paintings, the only secular and civil commission executed by Giotto in Padua

In the midst of Piazza della Frutta and Piazza dell'Erbe rises the Palazzo della Ragione. The ancient Palazzo, which resembles a huge upturned ship, was built in the 13th century and served as the seat of the city courts and the covered market of Padua.

Until the fall of the Republic of Venice in 1797, the Palazzo maintained its functions as town hall and palace of justice, the purpose for which it served under the commune era in the High Middle Ages, the Carrarese Lordship and the Venetian domination. However, it was also a commercial seat, the only function held over time until nowadays.

The wooden roof in the peculiar shape of an overturned ship's hull was designed in 1306 by James of the Eremites, an Augustinian friar. It is the largest roof unsupported by columns in Europe. After being destroyed in 1756 by a tornado, it was rebuilt by Bartolomeo Ferracina, a Venezian engineer, best known for the construction of the clock in Piazza San Marco in Venice and the reconstruction of the Palladian bridge in Bassano del Grappa.

Access to Palazzo’s upper floor, the Great Hall, was via four stairways that took their name from the markets below them: Scala dei Ferri (Irons staircase) and Scala del Vino (Wine staircase) in Piazza delle Erbe, Scala della Frutta (Fruit staircase) in Piazza della Frutta, and Scala degli Uccelli (Birds staircase) at the Volto della Corda (Rope Arch) - where traders who cheated on measures, swindlers, and insolvent debtors were punished with a rope.

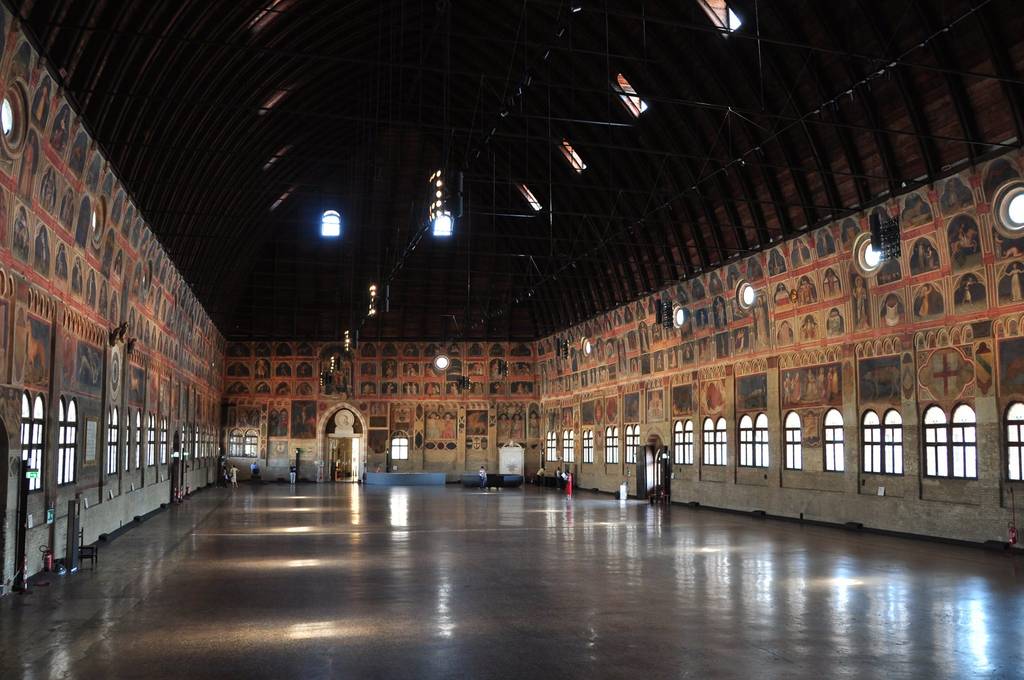

The Great Hall is a true miracle of architectural audacity. Measuring 80 by 27 meters and with a height of 40 meters, the Great Hall is believed to be one of the largest medieval halls still existing.

Originally it was divided into three rooms adorned with painted walls by Giotto. After the fire of 1420, the Venetian architects who undertook the restoration removed the internal partitions of the upper floor, forming the present great hall, Il Salone.

The great hall is decorated with around 500 frescoes, a collection among the largest and most complex known. A rich iconography that brings together astrological and religious symbols and numerous references to the Serenissima represented by the lion, as in 1420 Padua was already subject to Venice.

The Great Hall is not only decorated with many paintings, but it is also home to plenty of curiosities, like the nearly 6 meters tall wooden horse, a Roman tombstone, a Foucault pendulum, numerous clocks, sundials, and time measuring instruments. Among these is the famous Pietra del Vituperio, or the Stone of Failure, that once stood in the centre of the courthouse and on which insolvent debtors were humiliated and banished from the city. On the sides of the entrance door to the Hall are two Egyptian sphinxes brought to Padua in the nineteenth century by the Paduan explorer and archaeologist Gian Battista Belzoni.

The fresco cycle

The Great Hall, with its four large internal walls entirely occupied by frescoes, represents the most extensive cycle of Padua’s heritage. The pictorial cycle of the Palazzo represents the only secular commission from the civic authorities; the decoration was commissioned to Giotto by the Municipality of Padua about a dozen years after he completed the frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel, and it can be considered the public response to the previous private masterpiece.

The fourteenth-century chronicles report an incredible cycle of paintings on an astrological theme adorning the hall before the fire that broke out in 1420. However, the theme was re-proposed in the fifteenth century during the Venezian restoration. The painters Nicolò Miretto, Stefano da Ferrara and Antonio di Pietro, grandson of Altichiero da Zevio (who created the fresco cycle in the Chapel of St. James in the Basilica and the Oratory of St. George), respected the Giottesque model of judicial astrology inspiration and the charted influence of the planets on human affairs and disputes.

An important distinguishing characteristic of this cycle is its subject matter. There are no stories from the Gospels or the Lives of the Saints, but rather a massive secular almanac of enormous dimensions. This grandiose cycle comprises three hundred and thirty-three squares, organised on three superimposed registers along the upper part of the walls around the entire hall.

The entire upper cycle is divided into twelve sections corresponding to the months of the year. There is a correspondence created between zodiac signs, the planet and the constellation or ascendant that determines the character of those born under the related sign of the zodiac, the apostle associated with that month, a personification of the month, and the profession or the work performed during that month.

The lower register, which retains most of the original fourteenth-century frescoes, is a reminder of the Palazzo’s purpose since the thirteenth century. Their creation was inspired by the function of the different spaces into which this hall was once divided and by symbols associated with them. The walls carry visible traces left by the tribunal benches that once lined the hall. Separated by the animals, which identified the different tribunals and courts, the allegories and figures of saints in the lower area were intended to represent the divine grace that guides human nature.

Other extant fourteenth-century parts are The Judgement of Solomon, The Virtues, and The Trial of Pietro d’Abano. The latter was a respected Italian philosopher, physician, and astrologer who, in collaboration with Giotto, decided the iconography of the decoration within the Palazzo della Ragione. He was eventually accused of heresy and atheism. His trial is the theme in the aforementioned fresco, attributed to Jacopo da Verona, who created the fresco cycle in the Oratory of St. Michael. It also provides a realistic account of what a fourteenth-century courtroom must have looked like, complete with various interesting details.

Market under the Salone

Even if the close relationship between Il Salone and justice became obsolete over time, the function as commercial headquarters was maintained even 800 years later. The ground floor hosts the oldest European market. Dedicated initially to the commerce of a wide selection of food, clothes, spices, and jewels, today is mainly active in the food and beverage sector.

We welcome all contributions, no matter how small. Even a spelling correction is greatly appreciated.

All submissions are reviewed before being published.

Continue to changelog-

© 'Palazzo della Ragione, Padua/Italy' by HeinzDS is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 Attribution copied to clipboard Failed copying attribution to clipboard -

© 'Palazzo della Ragione' by Fuad Al Ansari is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 Attribution copied to clipboard Failed copying attribution to clipboard -

© 'Palazzo della Ragione - Piazza delle Erbe at night' by Fuad Al Ansari is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 Attribution copied to clipboard Failed copying attribution to clipboard -

We welcome all contributions.

All submissions are reviewed before being published.

We welcome all contributions, no matter how small. Even a spelling correction is greatly appreciated.

All submissions are reviewed before being published.

Continue to changelogWe welcome all contributions, no matter how small. Even a spelling correction is greatly appreciated.

All submissions are reviewed before being published.

Continue to changelogWe welcome all contributions, no matter how small. Even a spelling correction is greatly appreciated.

All submissions are reviewed before being published.

Continue to changelogCategory

Cost

-

The Palazzo della Ragione, built in the Middle Ages as the seat of the city courts, still hosts on the ground floor one of the oldest European markets

-

45 m

Piazza della Frutta, once called Piazza del Peronio, has been the commercial heart of Padua for centuries.

-

66 m

Piazza delle Erbe, one of the two squares that embrace the Palazzo della Ragione, is the temple of the Spritz cult and one of the most popular socializing places in Padua.

-

The Church of San Clemente is a small Baroque-style Roman Catholic church with an ancient history overlooking the Piazza dei Signori.

-

118 m

Palazzo Moroni, the usual name for the Municipal Buildings, is a complex of buildings in the city’s heart that house the offices of the Municipality of Padua.